The Vampire, A Mythical Monster For Eternity

By Victoria Hurtado

Plato: “There exists in every one of us, even in some reputed most respectable, a terrible, fierce and lawless brood of desires, which it seems are revealed in our sleep” (Plat. Rep. 9.572b)

Let’s Take a Walk to the Wild Side

A common belief in almost all societies and mythologies is the existence of creatures with human and animal traits, a hybrid mixture recalling our suspected double condition. It refers to the nature-culture dualism quite ubiquitous in European collective representations. Sigmund Freud in Totem and Taboo contrasts how the unruly impulses of nature are denied and controlled by culture. In antiquity, the Greeks characterized ambiguous and menacing beings lurking outside the civitas such as centaurs, satyrs and nymphs as 'savages'. Roger Bartra in Wild Men in the Looking Glass notes: “In Greco-Roman mythology, nature threatened culture with the exuberance of fantastic wild beings, inhabitants of the forests, the mountains, the islands and the seas […] the wild figures embodied a blend of nature and culture” (Bartra 1997, 43). Next of kin is the beast with different dangerous connotations: it was a name for the Antichrist and, as an adjective, depicts a cruel person whose behavior is uncontrolled. This metaphorical use is also shared by monsters that according to scholars are characterized by immoderation and deviation from the social rules. In the Middle Ages, a Christian imaginary coexisted with beliefs inherited from paganism. Many legends and myths spread by Bestiaries manuscripts, where descriptions of fabulous creatures were common and have survived to this day. It is believed that the dragon, from Latin draco, originally came from the ancient Near East. It was associated with an incarnation of the Devil created to cause chaos and suffering; in the Book of Revelation, Satan is described as ‘the great dragon’ and ‘the ancient serpent’. Despite this, it often appeared as a symbol of power in medieval heraldry. Throughout the ages of exploration, this European concept of ‘savage’ was used for the exotic counterparts. Bartra holds that: “the man we recognize as ‘civilized’ has not been able to take a single step without the shadow of the wild man at his heel” (Bartra 1997, 3).

1. Martin Schongauer, Saint George, c. 1480-1490. Engraving.

Monsters Inside and Out

During the 18th and 19th centuries, despite scientific discoveries and greater control over bodies and minds, monsters kept their place in the social imaginary. Already in the 17th-century English philosopher Thomas Hobbes in Leviathan used a Latin proverb: Homo homini lupus est to describe a state of nature, where humans would fight as wolves against each other; as if below the surface, the ‘animal nature’ could always break the cultural veneer. The normative construction of the philosophical, moral and political principles in which the superiority of the European had been rooted: rationality, self-control, moderation and balance, have been accompanied by a profuse literary and artistic elaboration of the figure of the monster. The Latin root of the term monstrare, meaning to warn, makes sense as under the influence of Freudian theories is exposed as the embodiment of our deepest fears and unconscious taboos, therefore being conceptualized as a symbolization of alterity. Its excessive nature defies rationality by transgressing cultural borders, as Joseph Campbell acknowledged in The Power of Myth: “By monster I mean some horrendous presence or apparition that explodes all of your standards for harmony, order, and ethical conduct” (Campbell 1988, 222). Being a projection of what is repressed, apparently despised and rejected, but secretly also envied because of its liberty. This analogy leads the social mandate of the 'taming of the animal’, which turns the 'other' into something similar to 'oneself', rendering it harmless and producing a certain stabilization of the Self. Modernity taught us how to control human drives, but still through monsters we recreate the mystery of that 'an-other' which, in a bewildering way, is also part of us. The ‘savage Other’ is conveyed in the rejection that produces in the collective imagination the metamorphoses between humans and animals, thus causing the uneasiness that timeless horror stories about werewolves or vampires produce in us.

In the field of anthropology, the umbrella term ‘monster’ as a cultural category is found ubiquitously in fieldwork. Considered as anomalies they exist in betwixt and between classifications as when something is neither good nor bad, or both. This symbolic domain was established by Victor Turner’s theory of liminality, a term derived from Latin limen ‘threshold’, regarded as a time and place of withdrawal outside normative patterns of social action.

2. Francisco Goya. The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters. (No. 43) from Los Caprichos. 1799. Etching with aquatint.

Yasmine Musharbash describes their powers in Monsters: “Transgressing states of animation is another way for monsters to disrupt taxonomies. The most prominent among these are the states of being dead or alive: ghosts, spirits, zombies, vampires […] undead monsters who drink the blood of humans—appear across time and space in countless cultures”. Another example is: “shapeshifters, creatures who are sometimes human, sometimes animal […] the monstrous body is often endowed with powers that far exceed what it should ‘naturally’ be capable of, including excessive speed and/or strength, the ability to become invisible or teleport, and so forth. These literal superpowers highlight the monster’s supernaturalness” (Musharbash 2021, 4).

The Threshold from Life to Death

The French anthropologist Lévi-Strauss argued in The Savage Mind that some common structures lead people everywhere to think in a similar vein, regardless of their social background. Among these is the need to classify and organize aspects of nature, its relationship with people and amongst beings. One of the most common means of classification is through the use of two dichotomic cultural notions, for example: dead/alive or day/night, thus converting differences of degree into differences of class. According to Lévi-Strauss a cultural way to handle the tension between those binary opposites is by the creation of myths. Besides there are interstitial categories that contain elements from both, and function as a link between two poles, one of which is perceived as dangerous and scary: like representations of an intermediate state between life and death. Veronica Hollinger in Fantasies of Absence: The Postmodern Vampire updates that criteria: “Postmodernism has undertaken to undermine and/or deconstruct innumerable kinds of inside/outside oppositional structures […] For this reason, the figure of the vampire always has the potential to jeopardize conventional distinctions between human and monster, between life and death, between ourselves and the other” (Hollinger 1997, 201).

The interaction between the visible society of the living and the invisible society of the dead is an anthropological constant. Stories of the 'revenants' come from a long time ago. Matthew Beresford explained in From Demons to Dracula. The Creation of the Modern Vampire Myth: “there are clear foundations for the vampire in the ancient world, and it is impossible to prove where the myth first arose. There are suggestions that the vampire was born out of sorcery in Ancient Egypt” (Beresford 2008, 42). Folklore scholars have found beliefs in every continent about creatures which do not die, leave their tombs, and return to feed on the blood of relatives and neighbours. Myths offer symbolic answers to questions about problematic issues related to the destiny of man, as the distressing separation between life and death. As Mary Y. Hallab observed in her book Vampire god, the allure of the undead in Western culture, they appeal to our fear of dying and hope for immortality: “the prime effect of vampire narratives is to create a symbolic and metamorphic way to comprehend and deal with death within the larger framework of life” (Hallab 2009, 7).

Most cultures believe that an individual's 'soul' continues to exist in some way after leaving their body. Death is considered a journey that should be prepared with the greatest care so that the deceased can leave the world of the living. The presence of ghosts has always been feared, which is why it has been ensured that funeral and burial rites are carried out without fail., with a double objective: to facilitate the path of the dead to their destination and to prevent a return. Paul Barber in Vampires, Burial, and Death reveals the fear of the corpse: “sources in Europe as elsewhere, show a remarkable unanimity on this point: the dead may bring us death […] to prevent this, the living attempt to neutralize or propitiate the dead—by proper funerary and burial rites, and, when all else fails, by ‘killing’ the corpse a second time” (Barber 1988, 195).

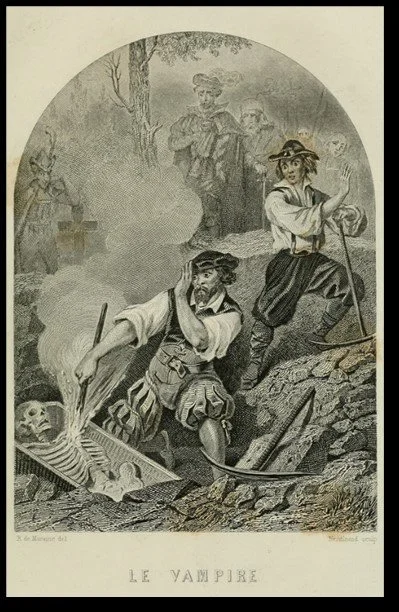

The undead became popular in Eastern Europe and in the Slavic tradition different terms were used to designate them: oboroten in Russia, upir in Poland and the Czech Republic, vampir in Bulgaria, vyrkolakas in Greece, strigoi in Romania, etc. The word vampire was added in 1733 to the German dictionary, a year later to the English dictionary one. In 1754 the work of Abbot Calmet, a scholar who clearly differentiated vampires from demons or spirits, established a quality that continues to this day: their materiality. Emily Gerard, a source for Dracula, divulged in 1888 an ethnographic description of her travel in The Land beyond the Forest. The Roumanians: death and burial—vampires and were-wolves : “More decidedly evil is the nosferatu, or vampire, in which every Roumanian peasant believes as firmly as he does in heaven or hell […] every person killed by a nosferatu becomes likewise a vampire after death, and will continue to suck the blood of other innocent persons till the spirit has been exorcised by opening the grave of the suspected person, and either driving a stake through the corpse […] In very obstinate cases of vampirism it is recommended to cut off the head, and replace it in the coffin with the mouth filled with garlic, or to extract the heart and burn it, strewing its ashes over the grave” (Gerard, 185).

3. Lithograph by R. de Moraine from 1864 showing townsfolk burning the exhumed skeleton of an alleged vampire. Book - Les tribunaux secrets.

Vampires, from Folk Storytelling to the Literary Genre

All myths began as an oral story, which details varied during their vernacular transmission; depending on the narrator and the social context they change over time. Myths are not rigid and immutable but fluid and interpretable, each declension is still part of a serial structure, updated through reformulations and different approaches. Jeffrey J. Cohen argues in Monster Theory. Reading Culture: “Monsters are never created ex nihilo, but through a process of fragmentation and recombination in which elements are extracted ‘from various forms’ and then assembled as the monster” (Cohen 1996, 11).

The literary imagination widens this range of variations and participates in the updating and diffusion of the myth. As in the case of vampires, conceived in the pre-literary stage, divulged from folk sources as superstitions, consolidated in the 19th century with Gothic literature, and spread in the post-literary stage thanks to the cinema and the media. As Carol Senf implies in The Ashgate Encyclopedia Literary & Cinematic Monsters: “the belief that reanimated dead bodies return to suck the blood of the living changes in Dracula into a metaphor that addresses the apprehensions of people living in a scientific and secular world. In this respect is an example of a modern myth, the evolution of which parallels other significant cultural transformations” (Senf 2014, 177).

4. Törtzburger Pass. Bran Castle. Lithograph by Ludwig Rohbock. 1883.

Count Dracula

Leonard Wolf in Dracula: The King Vampire states: “Dracula is a late Victorian example of the Gothic novel, which, from the time of its origin in eighteenth-century England, was meant to scare its readers” (Wolf 1992, 166). As such it holds some characteristic elements like the initial setting in a mysterious land and a malefic time, the noble villain, an old castle, damsels in distress, graveyards and coffins, the nocturnal terror, unearthly events and so on; all entangled in a mythical structure narrative like the confrontation with a monster, shapeshifting into bats and other creatures, and its death at the heroes hands or the primal fear of blood-sucking creatures. David D. Gilmore in Monsters Evil Beings, Mythical Beasts describes the basic stages in terror myths repetitive cycle:

The narrative component to consider in the monster's sudden irruption into the world… The typical story of attack shows a recurrent structure, no matter what the culture or setting. First, the monster mysteriously appears from shadows into a placid unsuspecting world, with reports first being disbelieved, discounted, explained away, or ignored. Then there is depredation and destruction, causing an awakening. Finally, the community reacts, unites, and, gathering its forces under a hero-saint, confronts the beast. (Gilmore 2003, 13)

Bram Stoker researched for seven years before publishing Dracula, where legends and myths are intertwined although he tried to give the impression of a realistic novel and gave the character a historical background.. As Carol Senf reveals: “… his father called himself Vlad Dracul after his initiation in 1431 into the Order of the Dragon, a chivalrous society dedicated to defending Christianity. His son consequently became known as Dracula, meaning son of Dracul or son of the dragon […] the fact that “dracul” also means “devil” in Romanian adds an additional intimidating connotation to the name” (Senf 2014,177).

An eternal fight of good vs. evil is in the plot and Dracula, to whom they refer as monster or beast, fortunately can be restrained by Christian paraphernalia. The male heroes enforce righteousness: Jonathan Harker, Dr. Van Helsing, Dr. Seward and two suitors of Lucy Westenra are the “hunters of wild beast” (Stoker, 333). Leonard Wolf in Blood Thirst: 100 Years of Vampire Fiction emphasized: “The antagonist, Count Dracula, is depicted as a satanic creature, the Primal Dragon, an apocalyptic monster and his pursuers as a sort of composite St. George doing battle with the dragon” (Wolf 1997, 5). Lucy was viciously attacked and become a new thirsty vampire. Her friend Mina whines in her diary: “… and if she hadn’t gone there at night and asleep, that monster couldn’t have destroyed her as he did” (Stoker, 277). A courageous character, she does not succumb completely to the hypnotic spell of the vampire and is saved despite her baptism of his own blood. In the Victorian society Dracula is also a sexual predator, his fantastical and deadly libido arouses mixed emotions that repels and fascinates at the same time. He represents what resists dying, the dangerous and the immoral; it is the inversion of the hero’s moral values and ethic, embodying an ideal behavior to be imitated.

A Gothic Fairy Tale

Dracula is a literary milestone in its endurance and impact on mainstream culture where the vampire sometimes has ceased to be the symbol of evil to become an ‘outsider’ or the protagonist. A comparison can be made with the allegedly true version, filmed by Francis Ford Coppola. As he assured in Bram Stoker's Dracula: The Film and the Legend: “Aside from the one innovative take that comes from history-the love story between Mina and the Prince-we were scrupulously true to the book” (1992, 3). But it is not, as Fred Botting in Gothic contends: “The much-publicised return of Dracula to cinema screens of the 1990s, for all its claims to authenticity, does not evoke the horror capable of expelling the evil, contaminating ambivalence of duplicitous images in which it, too, is enmeshed” (Botting 2005, 115).

5. The kiss of vampire. Illustration from Max Ernst's Une Semaine de Bonté. Collage novel. 1934.

The humanised vampire is in love with Mina, an incarnation of her former wife. The film's script concocts the tragedy of a heroic warlord damned by rejecting God, embracing the powers of darkness, becoming constrained in his immortal solitude and bloodthirsty cycle of life. Dracula is still a beast; however, he is finally redeemed from his eternal bloodsucker condition for the love of a woman who saves her soul. Under the motto: ‘Love never dies’ this horror and romantic fairytale was a blockbuster. As stated by Lindsey Scott in Crossing oceans of time: Stoker Coppola and the ‘new vampire’ film: “The film’s ability to attract female viewers was an essential part of the film’s overall success […] Although Stoker purists and avid horror fans were appalled by the changes that Hart and Coppola made to Stoker’s ‘classic’ novel, for those who embraced its hybridisation of horror and romance (and there were plenty), Bram Stoker’s Dracula opened up a broader space for the sympathetic vampire in the cinematic mainstream” (Scott 2013, 121)

The vampire has evolved as an antihero in the Byronic style and has ceased to be the symbol of evil to become a monster of seduction. In this way the myth acquires an affective value that will facilitate it to perpetuate itself. From here on, his success is unstoppable and some increasingly softened and deviant versions are taken on by the entertainment industry for mass consumption in the postmodern societies. Botting regrets: “the evanescence of one of modernity’s most powerful myths” […] “With Coppola’s Dracula, then, Gothic dies, divested of its excesses, of its transgressions, horrors and diabolical laughter, of its brilliant gloom and rich darkness, of its artificial and suggestive forms” (Botting 2005, 116).

Conclusion

As Lévi-Strauss made known, the structure of myths, belonging to the order of discourse, is part of a set that cannot be closed and is always open to innovation. Also, vampires change shape and as a symbol of otherness adapt to each new social environment and age. His creators update the legend of a monster that defies the passage of time and revitalize it to attract the new generations. In our postmodern culture the vampires have become mainstream, gone from being subjects of fear to becoming objects of desire, even laughter. The stark bloodlust beast conceived by Bram Stoker has been romanticized, glamorized, defanged and conveniently revamped by the cultural market to target the different consumer niches, stripping it of its exceptional alterity. However, Dracula has never run out of print, his undeadness appeals to a suppressed fear of dying, the most enduring taboo. It seems to be inexhaustible and will keep coming back as long as we need a mythical mindset and a desire for immortality.

Victoria Hurtado graduated with a BA in Social and Cultural Anthropology at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (UAM) in 2012, and then completed an MA in Public Anthropology in 2014, being her field research and dissertation about Gothic subculture. She has regularly participated in Madrid’s Gothic Week (SGM) – an annual cultural multidisciplinary festival- also given a talk at the Museum of Romanticism in 2011. She has presented at the annual Congress on art, literature and urban gothic culture hosted by the Universidad Complutense de Madrid (UCM) from 2017 to 2021. She has published for the Spanish Mentenebre and Ultratumba magazines and the academic journal Herejía y Belleza. In 2018 and 2022 she took part at the 14th and 15th International Gothic Association Conference

Contact: hurtado.vicky@gmail.com

Bibliography

Barber, Paul. 1988. Vampires, Burial, and Death. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Bartra, Roger. 1997. Wild men in the Looking Glass. The Mythic Origins of European Otherness. Michigan University Press, Ann Arbor

Beresford, Matthew 2008 From Demons to Dracula. The Creation of the Modern Vampire Myth. Reaktion Books Ltd.

Campbell, Joseph. 1988. The Power of Myth. Editorial Doubleday, New York

Cohen, Jeffrey Jerome. 1996. Seven Theses in Monster Theory: Reading Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Coppola, Francis F. and Hart, James V. 1992. Bram Stoker's Dracula: The Film and the Legend. Newmarket Press, Inc., New York.

Freud, Sigmund. 1950. Totem and Taboo, New York: W.W. Norton

Gerard, Emily.1888. The Land beyond the Forest. 2 vols. London: Will Blackwood & Sons.

Gilmore, David D. 2003. Monsters Evil Beings, Mythical Beasts, and All Manner of Imaginary Terrors. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Hallab, Mary Y. 2009. Vampire god, the allure of the undead in Western culture. State University of New York Press, Albany.

Hollinger, V. 1991. Fantasies of Absence: The Postmodern Vampire. In J. Gordon & V. Hollinger (Eds.), Blood Read: the Vampire as Metaphor in Contemporary Culture. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press

Lévi-Straus, Claude.1963. XI The structural study of myth. In Structural anthropology. Basic Books, In c., Publishers, New York

Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 1966. The Savage Mind. Chicago, Illinois. University of Chicago Press

Musharbash, Yasmine. 2021. Monsters. In The Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Anthropology, edited by Felix Stein. Online: http://doi.org/10.29164/21monsters

Plato, The Republic, 2007. Desmond Lee (Translator) Penguin Classics.

Radu, Raymond; T. McNally, Florescu. 1994. In Search of Dracula: The History of Dracula and Vampires. Houghton Mifflin Company.

Scott, Lindsey. 2013. Crossing oceans of time: Stoker Coppola and the ‘new vampire’ film. Chapter. 7. Representations of vampires and the Undead from the Enlightenment to the present day. OGOM. Manchester University Press.

Senf, Carol. 2014 Dracula. In Ashgate Encyclopedia Literary & Cinematic Monsters. ed. Jeffrey A. Weinstock.

Stoker, Bram. 1897. Dracula. Westminster. Archibald Constable and Company.

Turner, Victor. 1974. Liminal to Liminoid. In Play, Flow, and Ritual: An Essay in Comparative Symbology. Rice Institute Pamphlet - Rice University Studies.

Wolf, Leonard. 1992. Dracula: The King Vampire in Bram Stoker's Dracula: The Film and the Legend. Newmarket Press, Inc., New York

Wolf, Leonard. 1997. Blood Thirst: 100 Years of Vampire Fiction. Oxford University Press, Inc.

FILMOGRAPHY

Bram Stoker's Dracula (Francis Ford Coppola, USA, 1992)

“The Making of Bram Stoker's Dracula ‘Bloodlines’” Youtube, <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=szBO-Of5cOw>, [accessed1st October 2022]