Eiko Ishioka’s Costume Design for Bram Stoker’s Dracula: When The East Meets The West

By Tatiana Fajardo

I love the word “decadence,” all gleaming with crimson…It is made up of a mixture of carnal spirit and melancholy flesh, and al the violent splendors of the Byzantine Empire.[i.i]

PAUL VERLAINE

1992 saw the release of Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula. With a script signed by James V. Hart, the adaptation of Stoker’s novel (1897) follows the doomed love story of Count Dracula and his beloved Elisabeta. By depicting the historic figure of Vlad the Impaler, the film combines two different periods: the medieval epoch in which Dracula ruled, and the Victorian decadent era with Dracula turned into a vampire both in his castle in Transylvania and in London streets.

In this dreamlike and poetic gothic fairy tale, one of the most significant features is the costume design by the late Japanese art director and graphic designer Eiko Ishioka (July 12 1938 - January 21 2012). Coppola and Ishioka had already worked together on the Japanese poster of Apocalypse Now, yet when Coppola offered Ishioka to create the costume design for the film she hesitated as she did not have any experience in the field. She had never read Stoker’s novel, either. However, when Coppola mentioned that the costumes would be the sets, Ishioka accepted.[i]

This essay will analyse some of the exotic and erotic designs of the film and the artistic influences behind them. [ii]The main focus of my study will be the intertwining of Western and Eastern cultures Ishioka emphasised in her costumes and their colours, and how they help develop the storyline. I will mainly explain the outfits worn by the characters of Count Dracula (Gary Oldman), Elisabeta and Mina Harker (Winona Ryder), Lucy Westenra (Sadie Frost), and Dracula’s Brides (Monica Bellucci, Florina Kendrick and Michaela Bercu). The costumes of the Crew of the Light, that is, Abraham Van Helsing (Anthony Hopkins), Jonathan Harker (Keanu Reeves), Arthur Holmwood (Cary Elwes), Quincey Morris (Billy Campbell) and Dr John Seward (Richard E. Grant) will be mentioned. For the sake of brevity, Dracula’s familiar Renfield (Tom Waits) will be omitted.

DRACULA: A KALEIDOSCOPE ILLUSION

When creating the character of the Count, one of Ishioka’s clearest ideas was that the vampire would not follow the tradition of Bela Lugosi and his tuxedo, or the sobriety found in F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horrors (1922) and Count Orlok. The bloodsucker now would be a man-beast with shape-shifting abilities. ‘The basic color scheme for Dracula was red, white, black and gold’.[iii] Working with dualities such as devil/angel, handsome/ugly or male /female, the vampire and his changing moods were now echoed in the colours he wore.

RED: DRACULA’S TAINTED BLOOD

The muscular armour in which Dracula is seen at the beginning of the film in 1462 emphasises his humanness. Dracula is perceived as the mighty warrior fighting the Turks to defend the Christianity the Order of the Dragon attempts to protect. The Order of the Dragon, founded in 1408 by Sigismund of Luxembourg, then king of Hungary and Croatia, was created following the military orders of the Crusades, and fought against those who oppose Christianity, specially the Ottoman Empire. The Order adopted Saint George as its patron saint, as the defeat of the dragon symbolized the religious and military ideals of the order. When Elisabeta takes her own life thinking Dracula dead, he becomes the drakul or dragon/devil who must be slain as in St. George’s Christian allegory. Dracula is depicted as the fallen angel Lucifer, who is abandoned by his God.

Fig 1. Photograph by Sarah Stierch (CC BY 4.0). Fig.2. Ishioka’s design © Keith Serins. Fig. 3. Gary Oldman in the film (CC BY 4.0) unknown author.

In the Victorian era in which Stoker wrote the novel, ‘the Ottoman Empire was in a steady decline, causing anxiety in London because the newly independent states on the frontier would likely move into alliance with Russia’.[iv] The diplomatic concern is echoed in both the novel and the film by Van Helsing evoking the Crusades in his chasing of the vampire. Since Stoker never travelled to Transylvania, he constructed the area as an ‘armchair Orientalist’,[v] and Ishioka maximises this blending of Western and Eastern cultures in her designs.

When Jonathan Harker encounters Dracula in Stoker’s novel, the Count is described as ‘a tall old man, clean-shaven save for a long white moustache, and clad in black from head to foot, without a single speck of colour about him anywhere’.[vi] Ishioka, as already mentioned, deliberately departed from this depiction of the aristocrat. Dracula is dressed in black as the ‘Dark Rider’[vii] in an armadillo suit while taking Harker to the castle, but Dracula’s official appearance as Harker’s client and host is an old man in red with a hairstyle inspired by the Kabuki theatre. The blurring of the vampire’s personalities begins with his iconic Oriental-Turkish robe. Aided by makeup designer Greg Cannom, who created the old man’s face, Ishioka stated that they ‘aimed to develop for Dracula a haunting aura of transsexuality. Since he lived in Istanbul as a child, the costume is influenced by Turkish style as Dracula himself would have been. The enormous train, conspicuous when Dracula rushes about the castle like a bat, was designed to undulate like a sea of blood’.[viii] Embroidered on the breast is the Order of the Dragon, Dracula’s identity, a symbol similar to a Japanese family crest which emerges all throughout the film.

Figs. 4, 5 & 6, Images from the film (CC BY 4.0) Creative Commons unknown author (s)

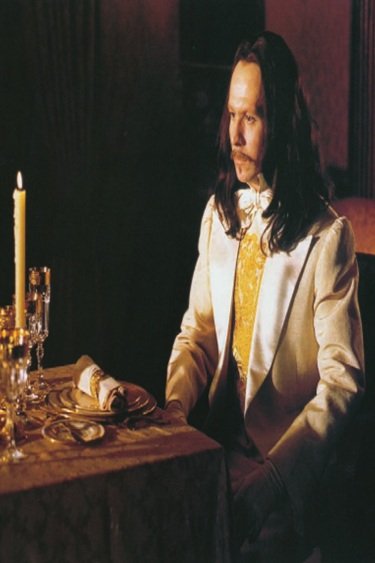

GREY/WHITE AND BLACK: THE DANDYISH SEDUCTION

In London streets, Dracula’s main appearance is as a dandy. Suits in grey, black and white highlight his elegance in his young persona. The fabric of the grey suit, imported from Europe, ‘is a kind of iridescent taffeta, which changes color depending on the angle. The dragon crest, mark of Dracula’s identity, is used in all the details: the tiepin, cuff links, and walking stick’. [ix] Dracula’s weakness for sunlight is presented by his Victorian sunglasses with bright blue lenses.[x] The vampire’s photosensitivity could be a symptom related to syphilis, a disease mentioned by Abraham Van Helsing in the film when he says that ‘civilization and syphilization have advanced together’.[xi] Dracula’s connection to a sexually transmitted disease, be it syphilis or AIDS as Coppola clarified,[xii] could at first be thought to appear by his wearing of the tinted glasses, yet there has been no historical source which clarifies the association between the coloured spectacles and the ailment despite some assumptions,[xiii] and Ishioka never commented on an intended linkage between the two concepts by utilization of the tinged lenses.

Figs 7 & 9: Pictures from the film: (CC BY 4.0) Creative Commons unknown author(s)

Fig. 8: Miniature of a young gentleman wearing spectacles with green-coloured lenses in silver frames, c 1807 in the De Witt Wallace Museum, Colonial Williamsburg

Interestingly, the vampire is associated with the dandy and the New Woman in the motion picture. As Charles E. Prescott and Grace A. Giorgio claim, at the time Stoker wrote his novel ‘conservative writers in the periodical press linked together two disparate figures, the New Woman and the dandy, as potential disruptors of the status quo.’[xiv] All those who threatened the established gender codes were ‘othered’, therefore it is logical that Dracula chases Mina Harker, as she breaks the social norms by working to obtain journalistic knowledge, for which she is considered to have a ‘man’s brain’. [xv]

Dracula’s appearance as Prince Vlad also echoes Charles Baudelaire’s ‘The Painter of Modern Life’ (1863) in which the French poet reckons that Dandyism ‘in certain respects comes close to spirituality and to stoicism’,[xvi] and its members are ‘a certain number of men, disenchanted and leisured ‘outsiders’, but all of them richly endowed with native energy,’ who ‘may conceive the idea of establishing a new kind of aristocracy’[xvii] in decadent ages. The new aristocracy Dracula proposes in his new religion of dandyism is a vampiric one in which he wants to experience death in the streets of London.

GOLD: THE LOVERS’ KISS

To create Dracula’s royal cloak, Ishioka based her design on Gustav Klimt’s paintings.[xviii] Coppola had already considered the Symbolist movement as an image of decadence perfectly suitable for the atmosphere of the film, and artists such as Gustav Moreau, Fernand Knopff or Klimt himself depicted an expressive language which, according to Coppola, ‘is a kind of evocative, poetic use of imagery, almost a dream state.’[xix] Ishioka abandoned historical accuracy when creating her designs, and she was also influenced by Art Nouveau and the Pre-Raphaelite and Neoclassical styles.

The coffin dress in which we see Dracula when Jonathan Harker discovers the boxes filled with earth from the castle is the same as the one in which we see him die when Mina kills him. The robe was painstakingly created by sewing all the scraps of fabric together. When Ishioka saw Klimt’s The Kiss (1907-08), she perceived the very Oriental flavour in the Western painting. Her robe for Dracula also evokes Byzantine art, therefore she experiments not only with distant places, but also with diverse epochs in a unique garment.

Fig. 10: Image from the film & Fig. 11: Byzantine dress: (CC BY 4.0) Creative Commons unknown author. Fig. 12: The Kiss by Google Art Project

In contrast with Dracula’s robe, the vampire hunters depict the 1890s, ‘an age when men were very macho. And Transylvania, where Seward, Holmwood, Morris, Harker, and Van Helsing are headed, is a land of fiercely cold climate. So “the Five Samurai”, as we called them, are dressed accordingly’. [xx] Consequently, they wear masculine outfits such as a fur mantle, a leather coat, a grey quilt, a leather cowboy coat, and an elegant cape. There is no doubt of their gender, no transsexuality is shown in the male humans, and the inclusion of furs suggests Russian influence and more blending of cultures in the story.

ELISABETA/MINA HARKER: DRACULA’S PRINCESS

In this tale with imagery reminiscent of Jean Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast (1946), Ishioka chose green to model both Dracula’s wife Elisabeta, whose dress shares Dracula’s crest of the Order of the Dragon, and Mina Harker (née Murray), who Dracula believes to be Elisabeta’s resurrection. In her Ophelia-like pose, Elisabeta wears a green dress with golden ferns, a symbol of love which Dracula also shows in his suits as soon as he meets Mina in London.

Fig. 13 & Fig.16: Images from the film. (CC BY 4.0) Creative Commons unknown author (s)

Fig. 14. John Everett Millais, Ophelia, circa 1851. Google Art Project

Fig. 15. Elisabeta’s dress. © David Seidner

‘Mina is sensible, strong-willed, intelligent, stoical, and naïve about sex. I felt green was the perfect color to symbolize this kind of woman and used a different shade of green in each scene for her, including a pale grey-green for her wedding to Harker. The high collars of the dresses reflect her chastity.’[xxi] When Mina stays in Lucy Westenra’s house, she is gradually influenced by her rich girl, and her neckline is lowered.

Fig. 17 & Fig.19: Images from the film. (CC BY 4.0) Creative Commons unknown author (s)

Fig. 18. Ishioka’s design of Mina’s dress. © Keith Sherins

The Eastern flavour is reminded in the scene in which Mina and Lucy peruse the Arabian Nights and the fascination Victorian England felt for the sensual Orient. At the time, the book and its translator Sir Richard Burton, whom Stoker met in the 1880s, were a scandal. Stoker pays homage to Burton and his vampiric stories in the Arabian Nights in the novel, when Jonathan Harker writes in Dracula’s castle that his diary ‘seems horribly like the beginning of the ‘Arabian Nights,’ for everything has to break off at cockcrow’.[xxii] Coppola, however, chooses the collection of folk tales to highlight Mina’s sexual naivety, and Lucy’s lustful tendencies.

At the end of the film, Mina’s wardrobe resembles Elisabeta’s style. When she travels with the vampire killers to Transylvania; her cape has a ‘strong Renaissance flavour, a Pre-Raphaelite look’, [xxiii] an echo to Elisabeta precisely just before and when the couple is reunited in Heaven after Dracula’s death at the altar and their image together is seen in the fresco of the chapel.

Nevertheless, perhaps one of the most remembered dresses worn by Mina is the red one on her date with Dracula. The only character in red in the film is Dracula, as the colour symbolizes blood. Yet for their date, ‘Dracula has this dress specially made for Mina, the object of his passionate love’. [xxiv] The colour also suggests that Mina will be transformed into a vampire.

Fig. 20. Image from the film. (CC BY) Creative Commons unknown author(s)

Fig. 21. Ishioka’s design of Mina’s dress. © Keith Sherins

LUCY WESTENRA AND THE BRIDES: THE DEVIL’S CONCUBINES

As previously mentioned, Lucy Westenra, Mina’s best friend, is presented as a lustful young aristocrat. Dracula hunts her while seducing Mina, and her Lilith-like character is displayed by her costumes. Lucy embodies the danger of a ‘sexually liberated girl’[xxv] in the Victorian time. As Roger Luckhurst clarifies, ‘the unnatural prospect of the sexually active woman had been associated with vampirism at least since Charles Baudelaire’s poem ‘Metamorphoses of the Vampire’’[xxvi] (1857), a poem in which a prostitute can smother a man in her arms. Lucy’s wantonness for wanting to marry three men is depicted in her party dress with the snake embroidery peppermint green. At a time when women suffering from anaemia were ‘encouraged to drink warm animal blood from slaughterhouses’, instead of doing so, ‘Lucy gains her symbolic multiple husbands through successive blood transfusions’[xxvii]. Ishioka employed orange for Lucy while she is lured by the vampire in her sleep or while he enters her room even with Arthur Holmwood allegedly protecting her.

Fig. 22. Lucy’s party dress. © David Seidner Fig. 23. Lucy in orange dress. © Ralph Nelson Fig. 24. Image from the film. (CC BY 4.0) Creative Commons unknown author (s)

Once Lucy is transformed and she becomes ‘The Bloofer Lady’ of the novel feeding on children, she is buried in her wedding dress. Ishioka’s source of inspiration for the iconic dress was the Australian frilled lizard.[xxviii] As it had already happened to Gary Oldman while wearing the armour, Sadie Frost had difficulties to move adequately while wearing the dress, and the stake skilling scene was changed: ‘At one time, she (Frost) practiced slithering down the crypt stairs like a snake, but the elaborate death costume made that impractical’. [xxix] Her makeup was emphasised after her death to highlight her vixen-like attitude. The moment when Lucy confronts the Crew of Light and throws blood through her mouth was a homage to William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973), a source of inspiration Coppola wanted to include in the film.

Dracula’s other concubines, the commonly known as The Brides, were a moment of creative disparity between Coppola and Ishioka. Since the film maintains a dreamy decadent atmosphere and absinthe plays an important role in it (as in Dracula and Mina’s date), Ishioka considered that the Brides could be the embodiment of the so-called ‘green fairy’, and her concept was three naked girls painted in green. She designed the women as succubi, but then reckoned that the result was more of ‘an art piece than a character’. [xxx] Coppola’s idea was that of a ‘deteriorating feel to the fabric,

Fig.25. Albert Maignan's Green Muse (1895), Wikimedia Commons. Fig. 26. Costumes of the Brides. © David Seidner Fig. 27. Alphonse Mucha Two Standing Women (1902), Wikimedia Commons.

like the shrouds of the mummies in the catacombs of Bombay’ in rich amber while having ‘extremely feminine robes, like the ones worn by women in paintings by the Czech poster-painter Mucha.’[xxxi] Here, the voluptuousness of the female vampires is linked to their garments as creatures from the East, a characteristic not described in Jonathan Harker’s journal in the novel:

In the moonlight opposite me were three young women, ladies by their dress and manner…Two were dark, and had high aquiline noses, like the Count, and great dark, piercing eyes, that seemed to be almost red when contrasted with the pale yellow moon. The other was fair, as fair as can be, with great masses of golden hair and eyes like pale sapphires.[xxxii]

The connection between Lucy and the Brides is found in the snakes: while the English aristocrat wears dresses with snake embroidery, one of the vampire’s hair is infested with snakes like a gorgon. The imagery of femme fatale through the serpents echoes Lamia, the child-eating monster of from Greek mythology, and the empusai, who seduced men to feed on their flesh.

In conclusion, this essay has analysed some of the most characteristic features in Eiko Ishioka’s costume design for Francis Ford Coppola’s film on Dracula. The intertwining of Eastern and Western cultures was one of the garments’ emphases as well as the use of colour in contrast with the stark image of the Count seen in cinema until then. The gothic fairy tale dwells in a decadent ambiance in which dreams and reality are blurred mostly by Ishioka’s outfits.

Tatiana Fajardo studies a PhD in Comparative Literature focused on Patrick McGrath’s narratives at the University of the Basque Country. She completed her MLitt in the Gothic Imagination at the University of Stirling, writing her dissertation on Patrick McGrath. Some of her essays have been translated into Swedish by Rickard Berghorn. She presented her study of Patrick McGrath’s latest novels The Wardrobe Mistress and Last Days in Cleaver Square at the International Gothic Association conference in July. Her essay “Patrick McGrath’s Ghastly New York: The Perfect Decaying Cityscape for Restless Minds” was published by Luna Press Publishing in 2021.

Bibliography

Baudelaire, Charles. ‘The Painter of Modern Life’, https://www.writing.upenn.edu/library/Baudelaire_Painter-of-Modern-Life_1863.pdf [Accessed 15th July 2022]

Coppola, Francis Ford and Ishioka, Eiko. Coppola and Eiko on Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Edited by Susan Dworkin. San Francisco: Collins Publishers San Francisco, 1992.

--- and Hart, James V. Dracula: The Film and the Legend. Edited by Diana Landau. New York: Newmarket Press, 1992.

Fitzharris, Lindsey. ‘Ray-Ban’s Predecessor? A Brief History of Tinted Spectacles’, https://drlindseyfitzharris.com/ray-bans-predecessor-a-brief-history-of-tinted-spectacles/ Prescott, Charles E., and Grace A. Giorgio. “Vampiric Affinities: Mina Harker and the Paradox of Femininity in Bram Stoker’s ‘Dracula.’” Victorian Literature and Culture 33, no. 2 (2005): 487–515. [Accessed 27th July 2022]

Prescott, Charles E., and Grace A. Giorgio. “Vampiric Affinities: Mina Harker and the Paradox of Femininity in Bram Stoker’s ‘Dracula.’” Victorian Literature and Culture 33, no. 2 (2005): 487–515. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25058725 [Accessed 10th July 2022]

Stoker, Bram. Dracula. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Filmography

Coppola Francis Ford dir. 1992. Bram Stoker's Dracula. Columbia Pictures.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula- Documentary (The Costumes are the Set): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_smVQFEMops. Alpha Tree Productions. [Accessed 20th October 2022]

[i.i] Paul Verlaine quoted in Coppola and Eiko on Bram Stoker’s Dracula, ed. Susan Dworkin (San Francisco: Collins Publishers San Francisco, 1992), p.24.

[i] Coppola and Eiko on Bram Stoker’s Dracula, ed. Susan Dworkin (San Francisco: Collins Publishers San Francisco, 1992), p. 21.

[ii] For further information, Bram Stoker’s Dracula- Documentary (The Costumes are the Set): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_smVQFEMops

[iii] Bram Stoker’s Dracula: The Film and the Legend, ed. Diana Landau (New York: Newmarket Press, 1992), p. 18.

[iv] Bram Stoker, Dracula, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), p. xxvi

[v] Stoker, Dracula, p. xxvi.

[vi] Bram Stoker, Dracula (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 18.

[vii] Coppola and Eiko on Bram Stoker’s Dracula, ed. Susan Dworkin (San Francisco: Collins Publishers San Francisco, 1992), p.36.

[viii] Bram Stoker, Dracula, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), p.41.

[ix] Coppola and Eiko on Bram Stoker’s Dracula, ed. Susan Dworkin (San Francisco: Collins Publishers San Francisco, 1992), p.81.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Coppola Francis Ford dir. 1992. Bram Stoker's Dracula. Columbia Pictures.

[xii] Coppola and Eiko on Bram Stoker’s Dracula, ed. Susan Dworkin (San Francisco: Collins Publishers San Francisco, 1992), p.89.

[xiii] Lindsey Fitzharris, ‘Ray-Ban’s Predecessor? A Brief History of Tinted Spectacles’, https://drlindseyfitzharris.com/ray-bans-predecessor-a-brief-history-of-tinted-spectacles/

[xiv] Prescott, Charles E., and Grace A. Giorgio. “Vampiric Affinities: Mina Harker and the Paradox of Femininity in Bram Stoker’s ‘Dracula.’” Victorian Literature and Culture 33, no. 2 (2005): 487–515. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25058725, p. 494.

[xv] Bram Stoker, Dracula, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), p.218.

[xvi] Charles Baudelaire, ‘The Painter of Modern Life’, p.10. https://www.writing.upenn.edu/library/Baudelaire_Painter-of-Modern-Life_1863.pdf

[xvii] Baudelaire, ‘The Painter of Modern Life’, p.11.

[xviii] Bram Stoker’s Dracula: The Film and the Legend, ed. Diana Landau (New York: Newmarket Press, 1992), p.127

[xix] Bram Stoker’s Dracula: The Film and the Legend, ed. Diana Landau (New York: Newmarket Press, 1992), p.70

[xx] Coppola and Eiko on Bram Stoker’s Dracula, ed. Susan Dworkin (San Francisco: Collins Publishers San Francisco, 1992), p.89.

[xxi] Coppola and Eiko on Bram Stoker’s Dracula, ed. Susan Dworkin (San Francisco: Collins Publishers San Francisco, 1992), p.61

[xxii] Bram Stoker, Dracula (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 31.

[xxiii] Coppola and Eiko on Bram Stoker’s Dracula, ed. Susan Dworkin (San Francisco: Collins Publishers San Francisco, 1992), p. 91.

[xxiv] Coppola and Eiko on Bram Stoker’s Dracula, ed. Susan Dworkin (San Francisco: Collins Publishers San Francisco, 1992), p.81.

[xxv] Coppola and Eiko on Bram Stoker’s Dracula, ed. Susan Dworkin (San Francisco: Collins Publishers San Francisco, 1992), p.54.

[xxvi] Bram Stoker, Dracula, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), p. xxi.

[xxvii] Bram Stoker, Dracula, p. xxi and xxii.

[xxviii] Coppola and Eiko on Bram Stoker’s Dracula, ed. Susan Dworkin (San Francisco: Collins Publishers San Francisco, 1992), p.70.

[xxix] Bram Stoker’s Dracula: The Film and the Legend, ed. Diana Landau (New York: Newmarket Press, 1992), p. 120.

[xxx] Coppola and Eiko on Bram Stoker’s Dracula, ed. Susan Dworkin (San Francisco: Collins Publishers San Francisco, 1992), p.44.

[xxxi] Ibid.

[xxxii] Bram Stoker, Dracula, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 38.